Durable request reply

The article explains a simplified distributed system based on message passing with a durable request–reply paradigm. The examples are drawn from Kafka, a distributed commit log implementation. The Reactive Manifesto outlines the main characteristics of a message-driven architecture.

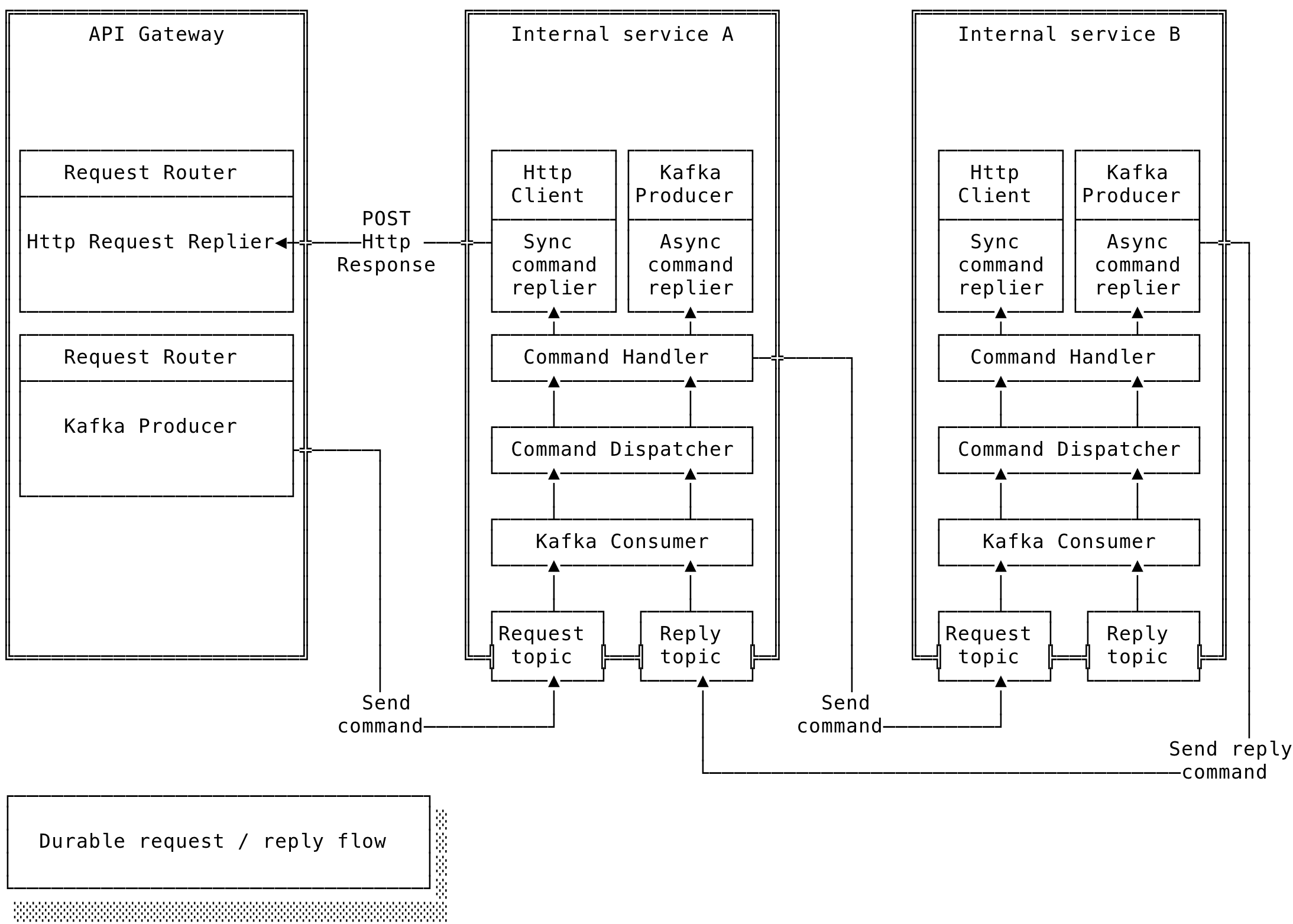

The system design diagram below provides a bird's-eye view of an exemplary microservice architecture:

Each of the following sections describes key system components.

API Gateway

The API Gateway is an infrastructure pattern that connects external clients with internal services. It can be implemented using non-blocking frameworks such as Elixir, Spring WebFlux, Node.js, or Zuul 2. Most major cloud providers, including Amazon and Google, also offer API Gateway as a managed service. The development team should choose the tool that best fits the project's budget and architectural requirements.

The responsibilities of an API Gateway vary by system. The most common include:

- Request routing

- Rate limit/throttling

- Security

- SSL termination

- Token translation

- Logging

- Caching

- Load balancing

- API monitoring and analytics

- Resource aggregation

An important aspect of the API Gateway is the request router, which directs incoming API requests to the appropriate internal services. By introducing this façade layer in front of services, each service remains isolated: the contract with external clients can stay stable even as internal services evolve. Ideally, services should communicate through message passing, where messages act as commands dispatched to the appropriate service.

Request handling flow

The overall request-handling flow is as follows:

-

Accepting an API request is the first step in the routing flow. Next, the system creates an in-memory request descriptor—a data structure that holds two things: a correlation ID and an HTTP request handle.

- The correlation ID uniquely identifies the HTTP request.

- The HTTP request handle is a promise-like object used to send the response back to the client.

Together, these can be stored in a map for fast lookups.

-

Creating a command A command consists of two parts: payload and headers.

- The payload is extracted from the incoming request.

- The headers contain origin details, including:

- communication type (synchronous or asynchronous)

- reply-to location (a REST URL or reply topic name)

-

Sending a command to a service The command is serialized into a Kafka record and published to the appropriate request topic on a Kafka broker.

-

Command handling Internal services consume commands from designated request/reply Kafka topics and execute the corresponding business logic.

-

Sending a reply command to the originator After a service finishes processing a command, it sends a reply command back to the originator (for example, the request router or another service).

-

Flushing the HTTP response The replier interface (part of the request router) handles service replies and returns HTTP responses to clients. It selects the appropriate client handle based on the correlation ID extracted from the reply command (see Accepting an API request for details). This interface is typically closed to public clients but available to internal services.

Using a non-blocking approach makes it possible to handle more HTTP connections with fewer resources. This increases system availability and provides greater elasticity.

The next section describes the durable request/reply mechanism for inter-process communication.

Durable request reply flow

Internal services support two communication types: synchronous and asynchronous.

Most development teams favor synchronous communication (typically REST) between internal and external services. However, using REST for communication between internal services can be problematic, as it introduces the following issues:

- Reduces availability.

- Introduces complexity when joining data owned by different services.

- Handling cascading failures and Http retries.

- Tight coupling between services.

Reliable message exchange between internal services should be asynchronous, durable, and transactional. To achieve these characteristics, the following patterns are commonly used:

- Commit log

- Kafka serves as a backplane for durable and asynchronous message exchange.

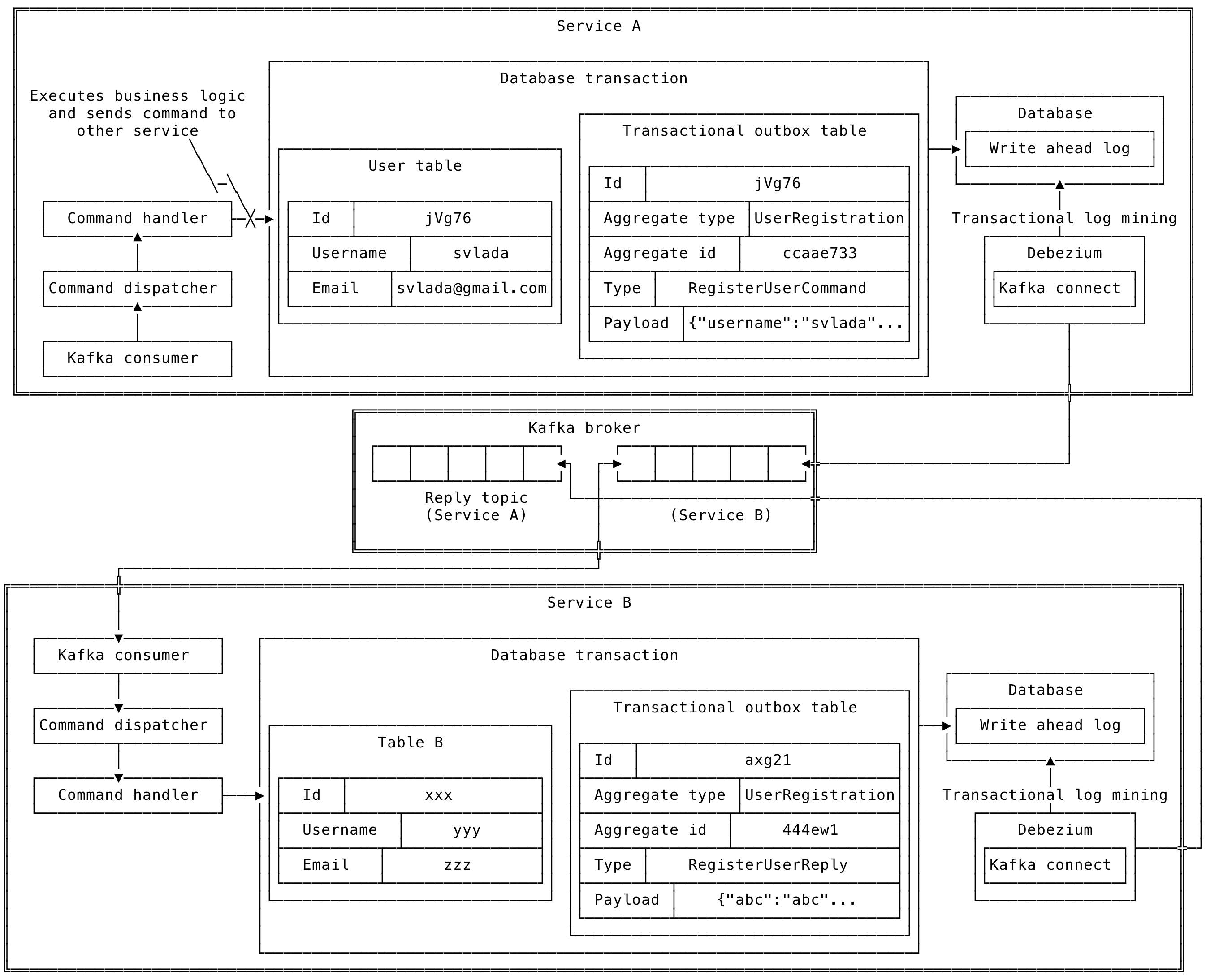

- Transactional outbox and log mining

- This pattern solves the problem of sending commands as part of a business transaction. A common use case is storing data in a local database while also emitting a command or event to Kafka, or invoking a REST API. Tools like Debezium are well-suited for transaction log mining in such scenarios.

To implement a durable request/reply mechanism, each internal service requires its own request and reply topic. Developers should also consider the number of partitions allocated per service, as partitioning directly impacts scalability. The number of partitions should be carefully planned with the future growth of each service in mind.

The durable request/reply flow is presented with the steps listed below:

- Service A (Kafka Producer): Sending command to Service B

- Set the following message headers: reply-topic-id of Service A and correlation-id.

- Serialize and post a message to request-topic-id of Service B.

- Service B (Kafka Consumer): Handle command

- Deserialize message.

- Process command and send ack/nack back.

- Send reply command to reply-topic-id of Service A.

- Consumer responsibilities: Reply topic

- Extract correlation-id from the Reply command.

- Use correlation-id to find Http connection handler. Note that the Http connection handler can run on a separate node or be a part of API Gateway.

When designing inter-process communication, it is advisable to follow an all-or-nothing approach (i.e., atomicity). This pattern has been well known and widely used for decades in database servers. A good definition comes from Wikipedia:

All the write operations within a transaction have an all-or-nothing effect, that is, either the transaction succeeds and all writes take effect, or otherwise, the database is brought to a state that does not include any of the writes of the transaction.

A common use case is committing a business transaction to the local database while reliably dispatching a command to a Kafka broker. The command should be dispatched only if the transaction succeeds.

The following are possible approaches for tackling this problem:

Use KafkaProducer to send command to a broker inside of business logic transactional context

@Transactional

fun businessTransaction() {

saveToDatabase()

dispatchCommandToKafka()

}Pros

- Easy to implement.

Cons

- Network failures can cause rollback of local transaction.

- Code is occuping expensive database connection for non-db work accross network.

Use KafkaProducer to send command to a broker outside of business logic transactional context

@Transactional

fun businessTransaction() {

saveToDatabase()

}

fun methodA() {

saveToDatabase()

dispatchCommandToKafka()

}Pros

- Easy to implement.

Cons

- Leads to error-prone code needed to check if local transaction succeeded or not.

- In case of service or Kafka broker failures no way to have a strong guarantee that command will be delivered.

Proper solution: Use transactional outbox

Commands are persisted in an outbox table as part of the same transaction as the business logic. Debezium, a transaction log miner, then picks up the record and pushes it to Kafka.

Some might argue that Debezium isn't necessary, and that Kafka Connect could be used to query commands directly from the outbox table. The drawback of this approach is the risk of missing commands due to transaction isolation. If reliability is critical and you cannot afford to lose commands, a transaction log miner is the safer choice.

The following image illustrates the transactional outbox pattern:

Pros

- Atomicity

- Strong guarantees that if local transaction succeeded command will be eventually delivered to Kafka broker.

Cons

- Another component in system to manage (e.g. Debezium)

Sagas

Handling business transactions that span different services is done through orchestration and usage of the Saga concept defined by Garzia in early 1960. Transactional outbox is a useful pattern used to implement orchestration using Sagas.

How to handle and implement distributed transactions using the Saga pattern will be covered in the next article. Stay tuned!

References